Chapter i: Three Beginnings

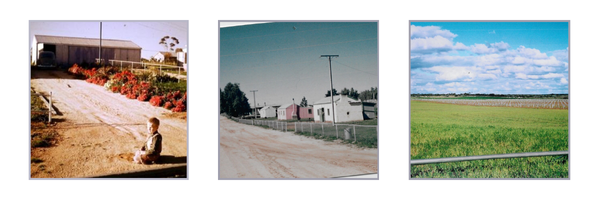

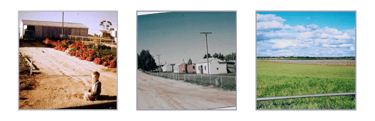

MONASH

January 1961

I arrived in January 1961, the second child of a second-generation fruit blocker, in a place called Monash in South Australia’s Riverland. It was a soldier settlement community: long straight rows of vines and fruit trees, irrigation channels cutting across the paddocks, and a collection of families who had been told that if they worked hard enough, they could coax a living out of hot dirt and river water.

That was the backdrop to my first years – sun, dust, and fruit. My father worked the block; my mother held everything else together. Like most kids, I had no sense of how precarious it all was. To me it was just “home”: the smell of irrigation, muddy banks on the Murray, and the quiet understanding that grown-ups always seemed tired.

BARMERA

1963

In 1963 we shifted to Barmera for a while – a short-term relocation “in transit from the block,” as I’d later describe it. At the time it was just another move. I didn’t know it, of course, but that in-between time marked the end of one way of life and the beginning of another. The next move would leave its mark for decades.

GERARD COMMUNITY

1964

When we moved again, it wasn’t just to a new street or town, but to a new kind of community. Gerard Aboriginal Community or reserve at it was called in those days. The river was still there, but the rules, faces, and expectations were different. For a small boy, it was both completely normal and quietly profound. I didn’t have language then for words like policy, settlement, reserve or mission. I just knew there were grown-up lines on the map that separated “us” and “them”, and that I often felt like I belonged on both sides and neither at the same time.

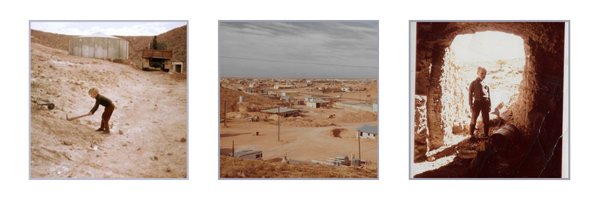

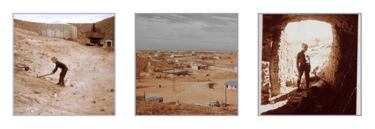

COOBER PEDY COMMUNITY

1965 - 1966

My first really remote community. Desert, drought, opal mines, and wide-open spaces. It’s only now that I can fully appreciate how unique that environment was. At the time, it was simply where we lived. Red dirt, heat that seemed to stretch on forever, and a landscape that didn’t offer much softness. Coober Pedy had a feeling that everything was a long way from everything else.

In what would also become an all-too-frequent pattern, my first year of school came with a sense of being slightly out of step with everyone around me. New place, new kids, and very little that was familiar. I didn’t have the language for it then — being the odd one out — but it was already settling in. That rhythm of moving, arriving, adjusting just enough, and then moving again. School became less of a place to build friendships and more of a place I passed through as we packed up one chapter and headed into another.

Looking back, that early exposure to remote living shaped a lot: resilience, or maybe just the ability to get on with things because there wasn’t much alternative. Coober Pedy was the start of that — a childhood framed by distance and change, even before I understood what those things meant.

POINT MCLEAY COMMUNITY

1967

Another community and another school — Year 2 this time. Life on the Coorong, alongside Lake Alexandrina. The landscape changed again, but the pattern stayed the same: arrive, find your place as best you can, then carry on.

I only have a handful of memories from there, and none of them particularly bad. A few moments stand out, but mostly it’s just a sense of being near water, big skies, and that slightly disconnected feeling that came with each new move. It wasn’t dramatic or traumatic — just another shift in a childhood filled with them, and another reminder that stability was always temporary.

GERARD COMMUNITY

1968 - 1973

By 1968 we were moving yet again. At least this time it was back towards where the story had started – familiar river, familiar red-brown paddocks, different angle. Another school. Another set of kids to work out. I was still in primary school, but by Year 3 I was already on my third school. The pattern was becoming clear long before I had the words to describe it.

We settled, for a while, on a couple of thousand acres with the Murray River as a playground. That part, I loved. There was space, real space – not suburban backyards but long dusty tracks, irrigation channels to jump, and stretches of riverbank where a child could disappear for hours and turn up again only when hungry or sunburnt. It was a good way to grow up if you liked being outside and didn’t mind mud, heat, or the occasional snake.

The harder part was school.

Winkie Primary was where I finished primary school, but I don’t remember it as an especially uplifting place. It was my third school by the time I was eight or nine. I’d learnt how to arrive halfway through other people’s stories: friendships already formed, pecking orders already established, teachers who had seen kids like me come and go each year. I was always catching up – names, rules, the local jargon of the playground.

I had, even then, a foot in two camps. At home and in the community, I’d absorbed a certain way of seeing the world – shaped by soldier settlers, working-class realities, and the particular mix of families and cultures along the river. At school and sport I learnt, often painfully, that “reserve kids” were seen differently. You could be friendly, good at a game, even liked in patches, but you were never entirely of the place. You were from somewhere else.

At the time it just felt like awkwardness and a vague sense of not quite fitting. Looking back, I can see the early outline of a much larger pattern: movement as normal, belonging as fragile, and the sense that the map under my feet was always slightly redrawn just as I’d started to understand it.

For a boy in the 1960s, though, it was just life. Fruit blocks, river water, hot summers, and yet another set of classmates to figure out

By the time the 1970s rolled in, we were firmly part of the Gerard community. On paper it was 1970–73; in my head it’s mostly remembered as river, red dust, and the growing awareness that the wider world had a set of rules about who belonged where.

I was still at Winkie Primary for most of that time, Grades 3 to 7. It wasn’t glamorous – small rural primary schools rarely are – but it was the longest stretch I’d had in one place. Same school, same bus, same teachers for more than a year in a row. After moving so often, that kind of stability felt odd.

Gerard itself was a lesson in community long before I had any language to describe it. Families who knew each other’s business, lines of connection that ran deeper than anything in town, and a constant negotiation with government departments who saw the place through a very different lens. I didn’t sit down and think about “policy”, “self-determination” or “colonial structures”, of course. I just knew that life out there felt different – and that once again I was both part of it and slightly on the edge of it.

Winkie Primary was where I finished the primary years, but it never entirely felt like “my” school. I’d arrived as the kid from “over there”, and those lines are hard to erase once they’re drawn, especially in small rural communities where everyone knows which bus you get on and whose place you go home to. I wasn’t an outcast. I just wasn’t quite standard issue either.

By 1974 I’d done what every country kid eventually has to do: move up to high school. For me that meant Glossop High School – my first secondary school, one year and a bit, and then off again. Glossop was bigger, louder, and more complicated than anything I’d known at Winkie. There were more kids, more teachers, more rules, and more ways to get things wrong.

It was also my introduction to the idea that schools themselves had reputations – sporty schools, rough schools, academic schools. I wasn’t particularly academic, and while I loved sport, I didn’t automatically fit into one of the easy categories. I was still carrying that uneasy sense of being between places: part Gerard, part Riverland town, not quite one of the kids who’d grown up in the same house on the same street all their lives.

Three Beginnings

Part One — Coober Pedy: Fragments of the Early Years

My earliest memories are scattered — flashes of a place harsh, dusty, and unforgettable.

Starting School

I vaguely remember my first school days in Coober Pedy. I was in a school play as “Mr Bear Squashed-the-Lot,” Mum sewing a bear hood that left a stronger impression than the performance itself. The schoolyard was just a dusty patch beside the main street. I still remember seeing an Aboriginal man strike a woman there — a moment far clearer than any lesson.

Around the same time, Dad came home from a street fight — there were no police in town then — and showed us his padded ribs, broken in the scuffle. Life went on.

Home, Jail & Dugouts

Our house was wrapped with an enclosed veranda. Behind it, a dugout cut into the hill stored spare coffins among other things — normal enough to us then.

A tiny jail, a 10-by-10 purpose built structure from Woomera, stood a few hundred yards away. I mostly know its arrival from photos.

The Afghan Camel Driver

A single-room building near the jail was home to an elderly Afghan camel driver who had delivered water in the early years of Coober Pedy. I don’t remember him personally — just his presence.

Bare Feet & the Hospital

Shoes were optional. Once I kicked broken glass and ended up at the hospital over the hill. A small scar between my toes remains .

My Own Little Mine

I dug a small mine behind the house — a shallow hole I worked on for two years. Photos show me at five years old digging away.

A Missing Vehicle

A vehicle once disappeared out in the desert. The search centred around the community for days. Dad was involved. I never learned what became of it.

The Store Incident

There was a store on the community. I remember dad throwing a brick at a vehicle driving off from the store. I also recall dads landcover down the "camp" for quite a while as we could see all from the house. Years later I learned something had been stolen.

The Desalination Plant

A desalination unit was installed in the township, and we drank fresh water straight from the pipe one weekend — a novelty in that place. It was eventually removed.

Riding the Train

Dad once took Mum, my sister and me to Tarcoola to catch a train to Adelaide. At Port Augusta station, Mum stepped off to the shop. A train on the next line began to move, and I panicked, convinced ours was leaving without her. That fear imprinted the place on me — a station that would weave through my life again for decades.

These are the fragments of Coober Pedy that remain — incomplete, but enduring.

A bit in the middle - point McLeay

After we left Coober Pedy, we spent what I think was about a year in an Aboriginal community on Lake Alexandrina, near the mouth of the River Murray, not far from Tailem Bend. I don’t have many memories from that time, just fragments. I remember the monkey bars at school — I seemed to be pretty decent at them and liked the feeling of swinging around. That is, until the day I was hanging upside down by my legs, slipped, and landed flat on my face. Two black eyes for my efforts. It still makes me pause when I think about it — the ground under the monkey bars was concrete. No soft-fall rubber or bark chips like they have now. Different times.

Years later, when I drove past Narung School, I was surprised by how small and isolated it looked. It fits the pattern of my upbringing more clearly in hindsight than it ever did at the time.

The other clear memory is the big clean-up for Guy Fawkes Night. Dad, being very community-minded, used a tractor to help build a giant bonfire down near Lake Alexandrina. The whole community came — or at least that’s how it felt. I can still picture the fire and the sense of excitement that went with it.

And then there’s the sheep incident. We were moving a mob somewhere, and there I was — a fully committed six-year-old — walking behind what I assumed was the tail end of the pack. Turned out I’d wandered right into the middle and split them in half. The men thought it was hilarious. I didn’t. Funny how some moments stick with you

Part Two — Gerard: The Quadrangle & School Days

When we moved to Gerard, the memories sharpen. Childhood wasn’t cushioned — but it was full.

Cricket Under the Willow Tree

We played cricket under a large willow in the quadrangle where the white workers’ families lived. I was usually the youngest. I loved bowling . I once suggested painting the ball and stumps with fluorescent paint so we could keep playing after dark. It was a good idea. It never happened.

Kindergarten

I was told I could walk to kindergarten if I wanted to go. I tried once, turned back, and that was the end of it.

The Red Pushbike

I believe my bike was red. I rode it everywhere. Late in primary school, I rode all the way to school and back — kilometres of dirt road — and no one seemed remotely concerned. That was normal.

School Bus 244

Our yellow school bus — Number 244 — had fibreglass seats. At school we drank quarter-pint bottles of milk. Someone always overdid it. On the rough ride home, a thin stream of milk sick worked its way down the aisle — a memory stronger than most academic achievements.

Freedom and Self-Reliance

Spot, our dog, went everywhere with me. Dad tried to teach me rabbit trapping. We wandered fruit blocks, haystacks, sheep yards and machinery sheds. We didn’t mix much with the Aboriginal community on the other side of the oval — separate worlds that never overlapped except on the school bus and at school.

Fruit Blocks, Animals and Everyday Dangers

The fruit block across the road gave us oranges and stone fruit whenever we wanted them. Someone once caught a long-necked turtle; Dad buried an old bath in the garden for it, but it eventually escaped.

Dad built me a mouse house from a fruit box — one mouse escaped, and I proudly tried to show the remaining one to our orange cat. That ended as expected.

After school we’d sneak cigarettes under a tree beside the super shed — convinced our parents had no idea. Snakes were common around those sheds, especially tiger snakes. Dad would shoot them when he found them. One climbed the front screen door. Another coiled itself in the car shed.

The super shed had steel skirts to stop mice climbing the stilts. I once stood up too quickly under one, driving a spike of metal into my back. No hospital. Just a wash in the bath and a bandage. That was life.

Haystack Fire

The farm had a new hay bailer and the result was a long rectangular haystack. It burnt down burned down one year. The story was that kids were smoking alongside it — careless but not malicious. By the time anyone realised, it was gone.

Summer Cubby Houses and Go-Kart

Each Christmas dad took the tractor and dug an underground cubby house. He reinforced it with steel and corrugated iron, thin dirt thrown over the top, it was mostly safe I think. There was a tiny fireplace and chimney. We crawled in on our stomachs and had adventurer. At summer’s end, he filled it with the tractor, ready to start again next year.

Later he built a motorised go-kart using the boat’s Villiers motor and a welded frame. We drove it in the old quarry. I remember his effort more than the driving.

The Night of the UFO

One evening Dad and I were at home. Mum and my sister had been out. I was told to get in the car quickly and we all went off down the dirt road that led to the community. Over the years, the story became clear: Mum was convinced a UFO had followed her. She thought at first it was a neighbour’s car, but the lights rose into the air.

She believed that firmly to her final days.

I’m not sure what happened — but the moment became family folklore.

TV and the Moon Landing

We got a television around the time of the moon landing. My parents must have saved for it, because money was usually tight—never without what we needed, but not much extra. The timing makes me think they bought it specifically so we could see the moon landing at home.

I remember the TV being set up in the lounge room and all of us watching the broadcast together. I don’t remember the details of the event itself as much as the fact that it was on our own TV, in our own house, which felt like something new and important.

Around that same time, I had a cardboard cut-out of the lunar module from a magazine or newspaper insert. You punched out the pieces and folded them together. I don’t recall much about making it, just that it was connected to that moment.

After that, TV quickly became part of the daily routine. After school, I’d watch shows like The Munsters. Only much later did I realise just how much time in my life ended up being spent in front of screens. At the time, it was simply what you did once you got home—turn on the TV and settle in.

Growing Up Between Ages

There were other European families, some who remained lifelong connections. But no one was my age. I learned early to be comfortable alone. To think for myself. To act independently.