Chapter 2: too many schools

By the time the 1970s rolled in, we were firmly part of the Gerard community. On paper it was 1970–73 in my head it’s mostly remembered as river, red dust, and the growing awareness that the wider world had a set of rules about who belonged where.

I was still at Winkie Primary for most of that time, Grades 3 to 7. It wasn’t glamorous – small rural primary schools rarely are – but it was the longest stretch I’d had in one place. Same school, same bus, same teachers for more than a year in a row. After moving so often, that kind of stability felt odd.

Winkie Primary was where I finished the primary years, but it never entirely felt like “my” school. I’d arrived as the kid from “over there”, and those lines are hard to erase once they’re drawn, especially in small rural communities where everyone knows which bus you get on and whose place you go home to. I wasn’t an outcast. I just wasn’t quite standard issue either.

By 1974 I’d done what every country kid eventually has to do: move up to high school. For me that meant Glossop High School – my first secondary school, one year and a bit, and then off again. Glossop was bigger, louder, and more complicated than anything I’d known at Winkie. There were more kids, more teachers, more rules, and more ways to get things wrong.

Then came Port Augusta.

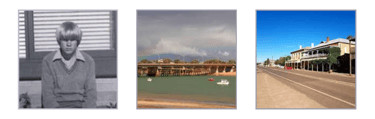

In 1975 we moved again: new town, new community, new addresses. For a while we lived in the caravan park, then on the community, and eventually in a house in town. That progression – from temporary to slightly more permanent to “proper” address – mirrored a lot of families’ journeys, but for me it mostly meant new schools, new kids and a whole new set of pecking orders to try to read.

Port Augusta was the first real town I’d lived in, and I was about may be twelve by then. It felt big, industrial, and slightly rough around the edges – power station, rail yards, trucks, pubs. There was a sense that things were happening there, people coming and going, shifts changing, trains arriving and departing. It was not a place that tried to be pretty.

I did a year at the town high school – another uniform, another set of teachers, another schoolyard to walk into on that awful first morning when you don’t know where anything is or who anyone is. I’d developed the usual survival skills by then watch first, talk later work out who to avoid pick the one or two kids who might be friendly try not to make a fool of yourself.

Despite all that movement, some friendships from Port Augusta have stood the test of time. There’s something about those mid-teen years – when everything feels raw and over-sized – that stamps people into your memory more deeply. You can go 30 or 40 years without seeing someone and still remember.

By 1976–77 I was at Caritas College for the final years of secondary school. That made number six in the school count. By that point I’d been to more schools than some of my teachers, which probably didn’t endear me to them. I knew the drill.

In the end I managed to get myself kicked out. Not as a grand act of rebellion, just as the cumulative effect of being restless, not particularly focused, and not really fitting the mould. I’m sure I was a frustrating student. Sitting still, taking notes, pretending to care about exams – none of that came naturally.

What did make sense to me in those years was sport, especially cricket. 1976 isn’t a year I remember in terms of grades or assignments; I remember it in terms of runs, wickets, and long hot Saturdays in whites on hard pitches. I played a lot of cricket and managed to make several town and regional representative sides. It was one of the few areas where moving around didn’t feel like a disadvantage. If you could bat, bowl or field, people were happy to have you, no matter which bus you got on at the end of the day.

Cricket also gave me something school didn’t: a sense of competence. At school I was the kid who didn’t quite fit. On the field I knew what to do. Most of the time, that felt more important.

By 1978, school was behind me and I’d started that awkward shuffle into the world of work. Like plenty of kids from my background, there wasn’t a carefully mapped career pathway. There were just jobs you could get, jobs you couldn’t, and stretches of unemployment in between.

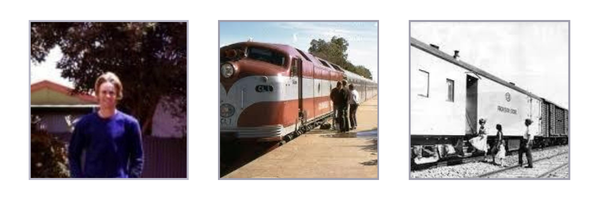

I drifted into the railways, picking up a couple of roles between periods of being out of work. I spent time in Provision Stores loading the old Tea & Sugar Train and also worked as a pay clerk. The clerical role sounded more respectable, but I was better suited to loading trains. There was something straightforward about physical work: turn up, move things from A to B, go home tired. No one cared about your school record; they cared if you turned up and did the job.

The Tea & Sugar Train itself was an education. It was more than just a rail service; it was a lifeline to the small settlements along the line, carrying supplies, people, stories and gossip. I didn’t romanticise it at the time – it was just work – but later I came to appreciate what that kind of service meant in places that didn’t have much else.

By 1979, the pattern of my late teens had set in: “Piss & Bad Manners”, as I later labelled it. In and out of work, restless, floating between Adelaide and Port Augusta. I never sat comfortably in the heavy industrial town drinking culture – the hard-drinking, hard-talking, union-hall-and-front-bar way of doing things. I understood it, but it wasn’t quite me.

too many schools

PORT AUGUSTA & CARITAS YEARS

Arriving Without a Map

Port Augusta was another move in a series of moves. Same routine: turn up, try to figure out how things worked, hope no one noticed I didn’t really understand the system. I knew it wasn’t permanent, so I didn’t try too hard. Teachers didn’t push very hard either.

We lived first in a caravan park inside an Aboriginal community. Dad was working away in the bush a lot. Mum kept us grounded and safe, sometimes a little too tightly. Later there was a community house, then the government-issued home tied to Dad’s job. All of it temporary, but stable enough.

Crossing the Bridge

Twice a day we crossed the bridge over the Gulf — home to school and back. Port Augusta was a railway town and I think that’s when trains became something I felt connected to. The station, the roundhouse, the railway workshops, the Tea and Sugar train — it all seemed big and organised and important.

Maybe I liked places where people passed through. Felt familiar.

The Railway Cafeteria

At lunchtime the whole school rushed across to the Railway Station Cafeteria. I tagged along, copying what everyone else did. Pies, pasties, noise, jostling, trying not to look lost. Years later I took my daughter back there. Funny how a place can stick even if the reasons don’t.

Friendship by Chance

I didn’t arrive with a backstory. One boy later said his memory of me was that “one day, this person just turned up.” That’s how it felt too.

Still, I made friends. Some lasted into my thirties. Some I still see now, forty-plus years later. Sport helped — without it, I would have been much more isolated.

Sport: A Place to Belong

Baseball gave me a home ground of sorts. There was a navy base nearby, and the Americans from Woomera were always a level above. Watching them play showed me the world didn’t end at the town limits. Sport was simple: catch, throw, hit. You belong if you can do your part. So I did.

Four, five, six days a week. It was something I could rely on.

Books, TV, Music, Lists

When things didn’t make sense socially, books did. Music too. The TV flickered through two channels — nothing like now. Lists helped keep things in order. Maybe they still do. A way to hold onto the pieces so they don’t disappear.

Authority and Questions

A bishop visited once and asked a question about belief. Everyone expected reverence. I found it amusing and laughed. That didn’t go down well. I didn’t reject anything outright — I just wasn’t wired to agree automatically.

That pattern stayed with me.

Searching for Familiar Faces

Decades later people started finding each other again — online and in person. Reunions. Conversations that skipped the awkward bits. Caritas held a 40-year reunion over three days. It was good. Proof that even temporary connections can last.

Leaving School, Working Instead

I left school early, came back, then was expelled. It wasn’t dramatic — just inevitable. I worked in a sheet-metal factory in Adelaide, then back to finish school, then off again. Railways. The Tea and Sugar store. Clerical work thanks to school friends. Factories in Adelaide and Melbourne. Mining out bush.

A series of starts and stops. Learning to turn up and get on with it.

Underpinnings

Even though I wasn’t disadvantaged myself, I often lived alongside people who were — in caravan parks, remote communities, on the margins of towns. Home was steady and loving, and that gave me space to notice when others didn’t have the same foundation.

Maybe that’s why later in life I could sit beside people who were struggling without looking down on them. I knew what it was like to feel outside the centre of things.